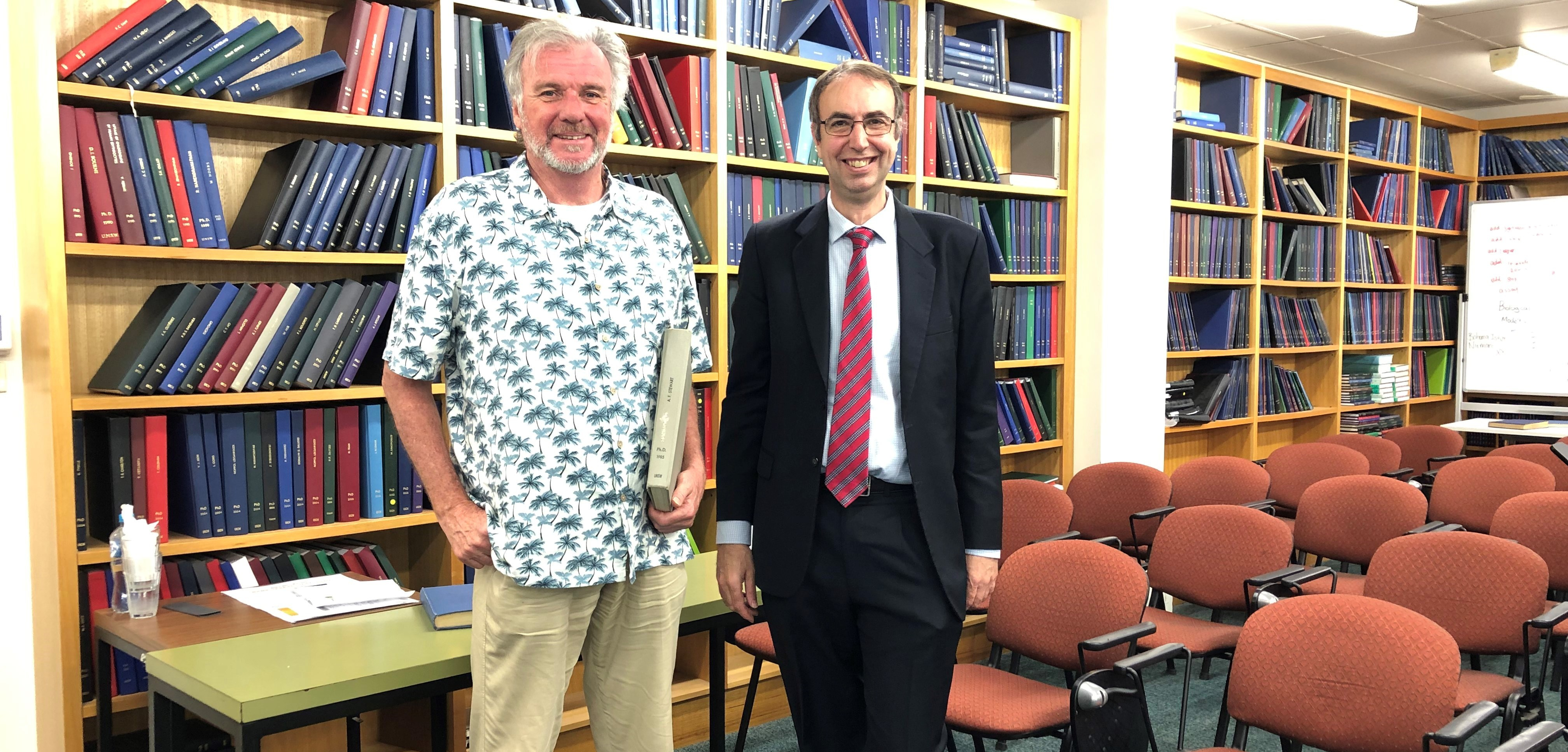

Merlin Crossley, Lab Head

One of the School’s successful alumni Francis Stewart makes a visit

One great thing about science is how international it is. Students graduate and travel all over the globe. But that does mean you sometimes lose track of them and you don’t always see their successes. Francis Stewart did his undergraduate and doctoral degrees at the University of New South Wales, Sydney in the 1980s and then headed over to Germany for a post-doc. He is now Chair of Genomics at the Center for Molecular and Cellular Bioengineering, TU Dresden, Germany. Because he thrived he never came back – except for the occasional visit. This week he dropped in and gave a seminar about his work.

Francis did his PhD with Tony McKinlay (who came back to hear his seminar). He must have been one of the first people in Australia to sequence DNA. He sequenced genes encoding milk proteins. He used the techniques that I used as a student, Maxam-Gilbert as well as Sanger sequencing. We found the bound copy of his thesis and looked at the gels. The quality was pretty good.

I first saw Francis when I attended an EMBO Conference on Chromatin and Transcription about 20 years ago. He stood out because he was the first person speaking who didn’t have an accent – I knew at once he must be Australian. I remember his talk then. He confidently but politely challenged the dogma. He was very careful and thorough in the evidence he presented. When you challenge the dogma you have to work harder to convince people.

I expect it is just that Francis is a particularly independent thinker but in Australia we sort of like to hope that we do educate students to show a cheerful disregard for perceived wisdom. I think Francis embodies that very well.

Now some science. The talk he gave was on chromatin and specifically Histone 3 Lysine 4 modification. When he began he talked about the symmetry of the nucleosome and asked whether histone modifications were also symmetrical, and if so how was that ensured. He showed that one of the enzyme complexes operated as a dimer (as a twin). To me that sort of explained it. But we were only ten minutes in so I knew the talk wasn’t over.

Next he tested the impact of mutating the dimerization interface in a tractable experimental system – yeast. In this system you can do carefully controlled experiments. These experiments won’t cure any diseases immediately, but they may well provide insights that inform so much of what comes next – as people are trying to understand human biology and tackle disease.

I won’t attempt to summarize the whole seminar but he showed some astonishing results that gently blew away the age-old concept I had learnt that histone marks were either activating or repressing and served as docking points for proteins that either turned genes on or off. This was how chromatin marks were first conceptualised and understood. This is how I have taught chromatin. It was a good, first, working model but I had been seeing only a small part of the picture.

Francis probed the limitations and talked instead about how the marks were important for indicating the history of gene expression. Perhaps for showing that a gene had been needed in the past and may be needed again – for priming. They could also be important for packaging and for quality control – if you want to coil up DNA neatly, then it’s probably important to have a symmetrical string. The marks may also be important for gene expression momentum and stable maintenance.

If you’d asked me how far mutating the interface of a protein (so it could no longer self-associate as a dimer/twin) would take us, I would never have imagined it would lead me to revise my whole understanding of the histone code and chromatin. But it has. That hour long seminar has influenced my understanding (and saved me hours of solo reading and thinking!).

After the seminar we had lunch in UNSW Sydney’s new staff lounge – our campus is great, with many good places to eat and meet, but I felt that only the lounge was appropriate for a special guest like Francis. The students, Francis’s supervisor, Tony, all talked about science and old times. It even transpired that we had close friends in common. One of my friends (who was a very great influence on me and taught me to juggle), who had worked at a bench near me when I was a PhD student in England and then with whom I shared a flat in Boston when we were both postdocs, was also a friend of Francis’s way back in the early days in Germany.

The scientific world is vast and some of the knowledge will last forever but our understanding keeps advancing and our circle of friends keeps expanding. Good science can be done anywhere and good scientists can go anywhere. We were delighted to have Francis back for the day and look forward to hearing of his future successes next time he visits.